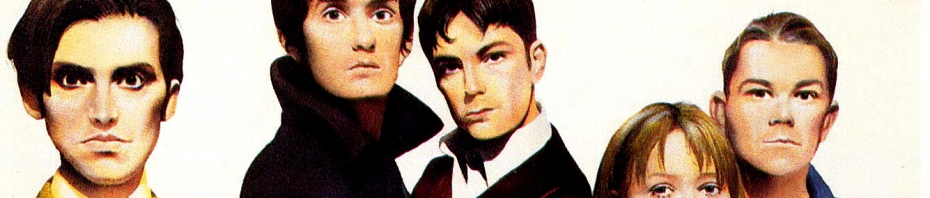

David’s Last Summer (‘His ‘n’ Hers’, 1994)

David’s last Summer at Pulpwiki

“And so with the sunshine and the great bursts of leaves growing on the trees, just as things grow in fast movies, I had that familiar conviction that life was beginning over again with the summer.”

F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby (1925).

“Rest is not idleness, and to lie sometimes on the grass under the trees on a summer’s day, listening to the murmur of water, or watching the clouds float across the sky, is by no means a waste of time”

John Lubbock

“Pulp once played a festival in Liverpool that was held in Sefton park. I remember seeing a Victorian glasshouse that had been left to its own devices after public service cuts. The plants were completely overgrown and the building seemed likely to explode at any moment due to the volume of vegetation inside.”

Jarvis Cocker – Mother, Lover, Brother

“We looked at each other irresolutely and then by common consent pushed through the rushes to the river bank. The river had been hidden until now. At once the landscape changed. The river dominated it— the two rivers, I might say, for they seemed like different streams. Above the sluice, by which we stood, the river came out of the shadow of the belt of trees. Green, bronze, and golden it flowed through weeds and rushes; the gravel glinted, I could see the fishes darting in the shallows. Below the sluice it broadened out into a pool that was as blue as the sky. Not a weed marred the surface; only one thing broke it: the intruder’s bobbing head.”

LP Hartley – The Go-Between

“When you get the first hot day of the year, I always get these pictures in my head. You think of all the things that happen in summer, swimming in lakes and building a tree-house and you get quite excited. But then you know that you’re not going to do all those things, you’re probably just going to end up working like you normally do. But it would be good just to have one summer that was like that one time and so I wanted to capture that feeling of those summers that seem to go on forever and you can do lots of things.”

Jarvis Cocker, French newspaper interview, 1994

“In summer, the song sings itself.”

William Carlos Williams

The idea of writing a song to evoke the endless summers of Sheffield in the late 70s had been in the air for quite a while. The first attempt, one of two songs named “My First Wife“, has already been covered, but undoubtedly there are many other attempts that fizzled out in the rehearsal room between 1987 and 1994. The version that emerges in the His ‘n’ Hers sessions has only a few snatches of lyrics and a theme in common, but the process of change itself has left its mark. It has an odd mish-mash structure, apparently being created out of a grab-bag of different snatches of music that didn’t fit anywhere else and were commandeered by this back-burner project. Along the way it also gained some fairly odd musical flourishes (including a sneaky lift) and a sympathetic producer who seems to have been determined to let his final touches be as near perfect as possible.

A snatch of lyrics and a theme may not sound like a lot, but David’s Last Summer is built around its narrative – as a short story rather than a song. That doesn’t mean that it’s an atmospheric bed for a poem – when it kicks in, after the lull of ‘Someone Like The Moon’, it actually sounds like the album is getting a second wind. DLS is the first pastoral Pulp song, and half-remembered it will always seem to be thoughtfully dramatic, so the sudden jump into this high-tempo mid-80s light jazz/funk always seems slightly jarring, and for a moment I’m tempted to think of it as a misfire. It’s not, though, it’s just a break from the expected shimmering, laidback feel of long hot summer films, a more realistic representation of the giddy feeling at the start of English summer holidays, and makes perfect sense as the start of our story.

We made our way slowly down the path that led to the stream, swaying slightly, drunk on the sun, I suppose. It was a real summer’s day. The air humming with heat, whilst the trees beckoned us into their cool green shade. And when we reached the stream, I put a bottle of cider into the water to chill, both of us knowing that we’d drink it long before it had chance.

Jarvis got the name of the song from a book in his school library called “Pennington’s Last Summer” which he saw but never read. Except he didn’t – K.M. Peyton’s classic young adult novel was called “Pennington’s Seventeenth Summer” though it was also published as “Pennington’s Last Term.”

Misrememberings like this always seem to be the wellspring of good art, and this is a great song title, vague and evocative. Who is this “David”? The lyrics constantly shift perspective – “we” “you” (female) “you (male) and her” “Peter” – but there’s never a David mentioned. Is this the kid called David from ‘Babies’? And why is it his last summer? Is this a character whose death makes the memory of this summer indelible, or is it a “last” summer before he leaves? The value of this summer is defined by how fleeting it is, and the possibility of death at the end sharpens this pressure.

If the year is a cycle of death and rebirth, then in summer we pass the peak and look down into the shadowy valley beyond.

This is where you want to be / There’s nothing else but you and her / And how you spend your time

The Last Summer is a perfected archetype, specific but general. It’s in Sheffield, in the 70s, but it could be anywhere and at any time. We’re caught between the innocence and carelessness of childhood and the nostalgia and awareness of consequences that come with adulthood. There’s a tension between the blissfully tranquillity of lying in the sun and daydreaming and the self-consciousness born from that freedom to think. We’re slipping into a slower pace, but under that soothing pastorality there’s an intense consciousness that makes the memories stronger, more vivid, more important.

We went driving

There are moments like this that are intensely filmic. Is it possible at this point not to picture the non-existent music video, the group heading down country roads in a convertible? We are in a moment, in a time, in a place. To be able to suspend disbelief like this is the measure of success for a piece like this. Was there really a summer like this? How much of it was spent bored or distracted? It doesn’t matter, of course.

The room smells faintly of sun tan lotion in the evening sunlight, and when you take off your clothes, you’re still wearing a small pale skin bikini. The sound of children playing in the park comes from faraway, and time slows down to the speed of the specks of dust floating in the light from the window.

Memory may be eternal and timeless, but real time is limited. In David’s Last Summer each moment is caught, frozen, before we suddenly skip forward to the next. The effect is that of flicking though a stack of polaroids. On summer holidays I used to focus intently on a single moment, think about how it would seem later as a memory, then, as it passed, think about how it was gone now and unchangeable. I don’t know if this is something other people did.

Time is limited, everything will die. To feel time passing is to lose it.

So we went out to the park at midnight one last time. Past the abandoned glasshouse stuffed full of dying palms. Past the bandstand and down to the boating lake. And we swam in the moonlight for what seemed like hours, until we couldn’t swim anymore.

The abandoned glasshouse is in Liverpool, the bandstand may be the one mentioned in the DYRTFT film. Memories are cut and pasted as much as music is – each section is different, but all somehow fit. Here we notice a snatch of melody which seems to be lifted from “Lisa (All Alone)” by Santo & Johnny. We’ve started at a casual fast pace, slowed down into contemplation, and now we’re speeding up again into an anxious close, but at no point has our journey seemed forced or unnatural.

As we walked home, we could hear the leaves curling and turning brown on the trees, and the birds deciding where to go for the winter. And the whole sound, the whole sound of summer packing its bags and preparing to leave town.

Pulp’s first attempt at a spoken song, Goodnight, took listeners gently down to road to sleep before shouting “boo” just as they were drifting off. It was a mean trick, but there was a good idea somewhere behind it. DLS doesn’t descend into horror, just a curdling, the love of the moment morphing into the impossible desire to hold on to it. First there’s the picked guitar, like September birdsong, the distant thunderclap of rumbling bass, then in comes Candida’s slightly out of tune Farfisa, like the distorted 8mm film of a beach holiday. Finally the pace starts to pick up, with Russell’s icy, discordant stabs of violin, as chilling as the first autumn winds, a storm rolling in, the sky darkening, the desperate feeling that the summer is over and there will never be another one like it, a final moment of crisis between the experience and the bittersweet memory.

And as we came out of the water we both sensed a certain movement in the air, and we both shivered slightly, and we ran to collect our clothes. And as we walked home, we could hear the leaves curling and turning brown on the trees, and the birds deciding where to go for the winter. And the whole sound, the whole sound of summer packing its bags and preparing to leave town.

…and up and up we go, taking off like a kite carried off into the storm. There is no more satisfying ending to a Pulp album, no better example of a story in a song. A hodge-podge of different sections, cobbled together over half a decade, it still works as high narrative drama, and (dare I say) art. Pulp would be soon be much bigger, and perhaps even better, but they’d never again simultaneously be this odd and this brilliant.