My Legendary Girlfriend (Separations, 1992)

My Legendary Girlfriend (BBC Soundcheck – Caff Single, 1992)

My Legendary Girlfriend (Music Video)

My Legendary Girlfriend (Live Video, The New Sessions)

My Legendary Girlfriend at Pulpwiki

My Legendary Girlfriend (Hit The North Soundcheck) at Pulpwiki

“That was about my girlfriend that I’d had in Sheffield. See, I never liked to mix business with pleasure. I’ve always kept my private life separate from music. So I’ve always gone out with girls who aren’t interested in music, and so people always asked me about my legendary girlfriend, because they’d never seen me with her.” – Jarvis in Record Collector #184, December 1994

Some groups break through suddenly, others take their time. Pulp took the journey as a series of uneven steps – and with My Legendary Girlfriend, we’ve reached one of the larger ones. In another world, this would have been their first big hit, and in a sense it was, but approaching it now it stands out as both half-forgotten (it has been rarely played live since around 1993) and – yes – legendary.

By 1989, Jarvis had been attempting to be a pop star for more than a decade, and failing by any measurable standards. The lyrics, the look and the music itself had all been rather hit and miss, and even when they been utterly wonderful, it had always been as the makers of outsider art of one form or another, always offering a challenge to any accidental listener. There had been experiments at making pop songs, sure, but they had been variously guilty of assuming popular music equalled dumbed down mulch and throwing ‘dark’ elements into the mix to counteract the pop fizz.

My Legendary Girlfriend is an astonishing record because it sweeps all of this away and reveals artists who are able to use popular forms to give their material greater depth rather than compromise it – to take what must have seemed to be odd fringe elements of their styles and tastes and tie them together to make something fresh and appealing. There are new things here, of course, but also much that has been covered before. Here are the night-time wanderings of Blue Glow and Being Followed Home, the breathy monologue of Goodnight, the separated lovers of Separations – but all tied together into a compelling, vivid story.

The catalyst for this is something the world of 1980s indie music had forgotten about – the groove. To the already unlikely-looking list of influences already mentioned we have to add Barry White – an artist much maligned in the last couple of decades (i.e. ‘The Walrus of Love’, Vic & Bob, etc) and remembered mainly for commercial love ballads rather than his smooth Love Unlimited Orchestra funk. My Legendary Girlfriend draws from the song of his you’re most likely to have heard – though if you’ve been listening to Heart FM they’ve been depriving you of the vital section. Before you continue reading, please have a listen here to the intro (the first 50 seconds or so) – the bass, the rhythm, the muttered vocals, the ‘we got it together’, sound at all familiar? Unlikely as it may seem now, this group of apparent misfits on the fringes of society had been listening to “You’re The First, The Last, My Everything,” tried jamming a version of it with Jarvis improvising lyrics on top and suddenly everything just clicked. For a while, the song was simply called ‘Barry White Beat’.

It wasn’t like funk was unheard of in Sheffield – this is the town and the recording studio that gave us Chakk after all – but earlier examples had generally been of the angular, moody sort – the kind you couldn’t dance to without doing a line of whizz and glaring around the dancefloor. My Legendary Girlfriend isn’t moody, though, it doesn’t strike poses. Disguised as it is by the MIDI-sequencing that took over much of Separations, that very human, gut-driven funk is still the driving force. To hear this clearly, listen to the live version released as a limited edition single by Bob Stanley of Saint Etienne the same year – nothing is sequenced here, just a group of musicians getting into a groove together, and the song is all the better for it.

This isn’t to do down the studio version of the song, though – they were able to retain this feel despite the track being partially sequenced (on new machines they were just learning to use, let’s not forget) – and just to top it off added all manner of synths, effects, odd noises and effects, all adding to the track in different ways. Even Russell’s wah-wah guitar sounds utterly integral, though his influence in the group was waning by this point. Overall the production, like the song itself, is wildly ambitious – but for once they’ve hit their target, shot the moon.

The best part of all must be Jarvis’s vocal – ironic as there are very little in the way of fixed lyrics here. As we get into the era of recording-first, performance-second, Jarvis would get into the habit of procrastinating over putting down lyrics until he ended up writing them on the day he recorded them, but here the improvisation is all out in the open. Every live performance starts basically the same, then veers off in a different (and usually very odd) direction – the version on Separations has “oh, Pitsmoor Woman!” and “no cheese tonight” – the BBC soundcheck version “girl over there with the hot pants on” and our first sighting of “that bloke who tries to sell you felt tip pens”. But despite this, there’s more of a story here than in almost any of their previous work.

We start in his girlfriend’s bedroom – they’ve “finally made it”, she’s asleep, but something’s nagging at him. He goes to the window, returns to wake her, and they go wandering around the city together – either in reality or in a dream – this is intentionally unclear. After that it’s all feeling and free-association, the verses wracked with desperate yearning (“let me in, let me come in”), the chorus a descent into relief – but sad, lonely relief, the girl now deserted, abandoned. Which part is “real”, then? Maybe neither, maybe everything after “I wonder what it means” is a fantasy, it probably doesn’t matter.

Jarvis spent a lot of the 80s walking around Sheffield in the dark, and when he was gone it seemed to still be the landscape of his dreams. So many of Pulp’s best songs are about “the city at night.” This is a step up from ‘Blue Glow’ though – the city isn’t just frightening but is also alive with hidden sexual intrigue – a magical realm where deserted factories and cooling towers represent a fantasy playground, one whose endless hidden mysteries they are free to explore. Owen Hatherly calls this the “sexualised city” – a place where sensuality opens a gap for fantasy to bleed into reality.

Because THIS is the vital element that makes it all work. Up to this point Pulp had assiduously avoided talking about sex in all but the most perverse and uncomfortable fashions – “My blood upon the tarmac / I tore the dress from your back” “They make love beneath Roger” – all that. Perhaps it was the move away*, or the freedom of release from his first long-term relationship, or maybe just Barry White, but suddenly sex is a source of wonder and excitement rather than worry. This isn’t a lyrical device either – it extends into every aspect of the performance. The pretence of the croon is long forgotten, and instead he’s using his vocal to let something out. After a decade of control it’s almost shocking to hear the pants and groans he puts into the performance. The sheer cheek of pretending he’s a sex symbol, the audacity to somehow pull it off.

Staple of the indie disco as it may or may not have been,** My Legendary Girlfriend has lost none of its vitality through the years. This is Pulp at the top of their game, the start of the band we love, their first undeniable classic, their “This is us, and we’re just getting started.”

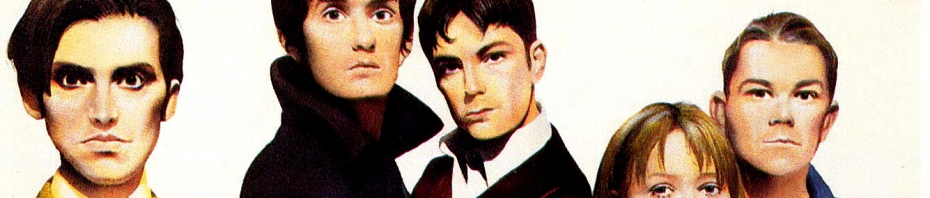

(A note on the video – it’s not a classic but a decent recording of a good performance, and that’s enough. Apparently it was a nightmare to make, but on the plus side Jarvis’s comments offer us a rare glimpse into the world of Pulp in 1991 – “There were quite a few false starts on this one. First we tried filming something in the room of the East End pub where the great train robbery was planned (don’t ask why). Unfortunately we didn’t light it enough and so ended up with mostly black film. I then shot some stuff of my girlfriend of the time but then split up with her and became too depressed to use it… hmmm. We were now in a difficult position as I had spent just about all of Fire’s massive £200 budget and had nothing to show for it. Unchained Melody was at number one at the time and I liked the way it used one performance of the song filmed from various angles as the video. So we decided to try and do something similar in the photo studio at St Martin’s. We blew the rest of the budget on a star-cloth background and I ended up having to make Nick a drum kit out of cardboard because we couldn’t afford to bring the real one down. Luckily, it worked.”)

*Unlikely as Jarvis has said he went through a sexual drought during his time in London

**It was already becoming a rarity when I started going in the late 90s. We’d hear that drumbeat, dash onto the dancefloor, then every time it would turn out to be ‘I Am The Resurrection’ instead.

Tags: barry white, caff single, city at night, funk, improvised lyrics, monologue, my legendary girlfriend single, separated lovers, separations, sexualised city